Why do so many people think we should be A CHRISTIAN NATION?

Come to think of it, why DO all those so-called patriots seem to hate the country?

[PLEASE NOTE: You may assume that a bold emphasis within a blockquote’s probably mine.]

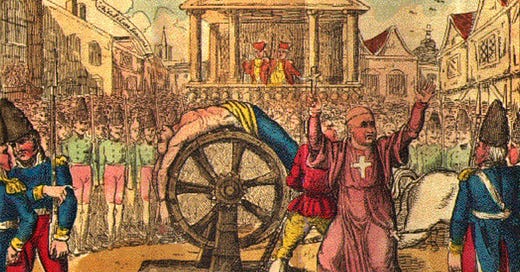

YEAH, THIS PROBABLY ISN’T REALLY WHAT OUR “JESUS-JIHAD-SQUAD” HAS IN MIND ... that is, GOP elected officials who talk about wanting the U.S. to become a “Christian nation”. Jean Calas, the man shown being executed on the wheel, ended up there essentially for living as a Protestant in the officially Catholic France, just thirty years before the Revolution. For Calas’s story, which sounds like a 1930s movie plot, click this link. (Wikipedia / Public Domain)

“THE CHURCH IS SUPPOSED TO DIRECT THE GOVERNMENT. THE GOVERNMENT IS NOT SUPPOSED TO DIRECT THE CHURCH. THAT IS NOT HOW OUR FOUNDING FATHERS INTENDED IT.”

That, according to the Washington Post, is what Rep. Lauren Boebert proclaimed in a Colorado religious service last June, just before her primary election:

She added: “I’m tired of this separation of church and state junk that’s not in the Constitution. It was in a stinking letter, and it means nothing like what they say it does.”

Nor, by the way, does the Second Amendment, an amendment I’m guessing she might like even more, but none of the amendments are really all that clear and, over time, come to mean what our courts interpret them to mean, the same legal principle that allowed her restaurant servers to pack pistols at work, even though they’re not necessarily members of any well-regulated militia — something I’d guess she’d have known had she stayed in school long enough to be qualified to do her present job of helping write our nation’s laws. Consequently, Steven K. Green, a professor of law and affiliated professor of history and religious studies at Willamette University, said that, Boebert is wrong.

“While the phrase separation of church and state does not appear verbatim in the Constitution, neither do many accepted constitutional principles such as separation of powers, judicial review, executive privilege, or the right to marry and parental rights, no doubt rights that Rep. Boebert cherishes,” wrote Green, the author of “Separating Church and State: A History.”

Nor, by the way, does the Constitution mention God, which one would suppose might make Boebert want to damn the whole damn document to hell.

But, yeah, okay, Boebert’s spokesman, Benjamin Stout, told PolitiFact that

"Christian principles have informed and guided lawmakers in America since its founding. The Congresswoman believes that that should continue."

"The Congresswoman does not believe in a theocracy, or an established religion set by the state," Stout added. "That’s exactly what the establishment clause protects against."

Although that seems to contradict what she said. Still, I’d more likely believe that if she had said it herself instead of leaving it to her mouthpiece. Maybe she had him say it to give herself some “plausible deniability”.

But Boebert is not alone, of course. This was in late July:

The Republican Party’s primary focus this year should be on making the political party one of Christian nationalism, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) said Saturday.

“I think that’s an identity that we need to embrace, because those are the policies that serve every single American, no matter how they vote.”

Though most Republican voters identify as Christian today, not all Republicans are and the number who do identify with this religion has been decreasing over the last few decades, particularly among younger voters, according to the Pew Research Center.

What’s going on here? Christian Nationalism may not be a viewpoint of the American majority, but it’s probably closer than you think:

According to the top line of the above survey, released in late October by Pew Research,

Three-in-five Americans believe the Founders meant the U.S. to be a “Christian nation”, while a little under two-in-five don’t...

But only roughly one-in-three Americans think it is one, while about two-in-three don’t...

And just under half of Americans believe it should be one, although a tiny majority thinks it should not be one.

(Yikes.)

So what if we did become a “Christian nation” — what would that even mean?

Essentially, that’s this week’s question.

First of all, we need to deal with the question of whether or not the Founders really intended the United States to be a “Christian nation”.

Mostly, even among those who believe in “Christian Nationalism”, there seems to be a general consensus that, no, none of the Founders thought there was any need for Christianity (or any other religion) to become the American “state religion” — and if you disagree with that, please say so in the comments.

Mostly, those who think we are a Christian nation or were meant to be one tend to think that, at most, the Founders based the founding on “Christian” values or the “Ten Commandments”.

But plenty of historians contend that the intention was to keep religion out of government affairs, at the very least on the national level, and many have argued that the wall has to keep each away from the other — that not only is the church harms government, but government is destructive to the church.

But in fact, I have not been able to find any evidence that any of the founders proposed that the new nation be a “Christian” nation. If you know of any, once again, please let me know in the comments.

To the contrary, the consensus I saw among the Founders considering the amendments seemed to be less about whether, but instead how to express the prohibition of mixing governmental into religion’s affairs, and vice versa.

GIVEN THAT MANY OF THE COLONIES HAD ALREADY HAD OFFICIAL RELIGIONS, AND EVEN SEEMED TO HAPPILY CONTINUE THESE AFTER THE REVOLUTION BEGAN, YOU MIGHT WONDER HOW ATTITUDES CHANGED SO DRASTICALLY ONCE THE TIME CAME TO WRITE A CONSTITUTION FOR THE WHOLE COUNTRY IN 1787,

... but James Madison may have had something to do with that.

Maybe he was influenced by the British parliament’s insistence back in the 1760s on taxing the colonists without their being directly represented by it, but once the colonies declared independence, Madison began pushing back on the idea of states having established churches.

Throughout the states, most of them were tied to either the Congregational Church in New England, or the Church of England (aka, Anglican, or, nowadays in America, Episcopalian) elsewhere, and the legal power of those institution’s to collect money from all citizens, even those not of that faith.

As a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, Madison continued to advocate for religious freedom, and, along with Jefferson, drafted the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. That amendment, which guaranteed freedom of religion and disestablished the Church of England, was passed in 1786.

While this insistence on ensuring religious freedom situation was constantly on Madison’s mind, it didn’t necessarily seem to be on the top of the to-do list of anybody else in the nation, although that national attitude may have transformed somewhat during his Virginia campaign, as related here by a Library of Congress exhibit:

The debate in Virginia in 1785 over religious taxation produced an unprecedented outpouring of petitions to the General Assembly.

This petition from supporters of Patrick Henry's bill in Surry County declares that "the Christian Religion is conducive to the happiness of Societies." ... "That a conscientious Regard to the approbation of Almighty God lays the most effectual restraint on the vicious passions of Mankind ..."

Yes, Patrick Henry, he of “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” back in the 1760s, was not quite as keen on everyone having the freedom to practice “Liberty of Conscience” two decades later.

But nor was that argument of his supporters that esteem for God restrains Mankind’s “vicious passions” always so visible, especially when perpetrated on Baptists who, along with some Presbyterians, were major opponents of state religion:

Many Baptist ministers refused on principle to apply to local authorities for a license to preach, as Virginia law required, for they considered it intolerable to ask another man's permission to preach the Gospel. As a result, they exposed themselves to arrest for "unlawfull Preaching," as Nathaniel Saunders (1735-1808) allegedly had done.

And not only arrest.

In Virginia, religious persecution, directed at Baptists and, to a lesser degree, at Presbyterians, continued after the Declaration of Independence.

The perpetrators were members of the Church of England, sometimes acting as vigilantes but often operating in tandem with local authorities. Physical violence was usually reserved for Baptists, against whom there was social as well as theological animosity.

A notorious instance of abuse in 1771 of a well-known Baptist preacher, "Swearin Jack" Waller, was described by the victim: "The Parson of the Parish [accompanied by the local sheriff] would keep running the end of his horsewhip in [Waller's] mouth, laying his whip across the hymn book, etc.

When done singing [Waller] proceeded to prayer. In it he was violently jerked off the stage; they caught him by the back part of his neck, beat his head against the ground, sometimes up and sometimes down, they carried him through the gate . . . where a gentleman [the sheriff] gave him . . . twenty lashes with his horsewhip."

And this, a few years later:

VIRGINIA’S RULING ANGLICANS BAPTIZE NONCONFORMING BAPTISTS IN A LOCAL RIVER ... “The Dunking of David Barrow and Edward Mintz in the Nansemond River, 1778. Oil on canvas by Sidney King, 1990. Virginia Baptist Historical Society”

David Barrow was pastor of the Mill Swamp Baptist Church in the Portsmouth, Virginia, area. He and a "ministering brother," Edward Mintz, were conducting a service in 1778, when they were attacked.

"As soon as the hymn was given out, a gang of well-dressed men came up to the stage . . . and sang one of their obscene songs. Then they took to plunge both of the preachers. They plunged Mr. Barrow twice, pressing him into the mud, holding him down, nearly succeeding in drowning him . . . His companion was plunged but once . . . Before these persecuted men could change their clothes they were dragged from the house, and driven off by these enraged churchmen."

But eventually, the harassment in Virginia backfired.

The persecution of Baptists made a strong, negative impression on many patriot leaders, whose loyalty to principles of civil liberty exceeded their loyalty to the Church of England in which they were raised.

James Madison was not the only patriot to despair, as he did in 1774, that the "diabolical Hell conceived principle of persecution rages" in his native colony. Accordingly, civil libertarians like James Madison and Thomas Jefferson joined Baptists and Presbyterians to defeat the campaign for state financial involvement in religion in Virginia.

Getting this passed in Virginia was actually such a proud accomplishment for Jefferson that he chose to have it engraved on his tombstone, along with his founding of the University of Virginia, but curiously, not mentioning he had once served as America’s president.

(Christopher Hollis via Wikipedia / Public Domain)

Madison also heralded it as worthy of a place in history:

Upon the passage of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786, James Madison wrote to its author, Thomas Jefferson: "I flatter myself we have in this country extinguished forever the ambitious hope of making laws for the human mind."

Nice plan, but no such luck. We still have those who nurse that hope, even today.

OH, AND REMEMBER ALL THOSE BAPTISTS WHO FOUGHT FOR A CHURCH-STATE WALL OF SEPARATION? YOU MAY (OR MIGHT NOT) BE HAPPY TO KNOW THAT THEY’RE STILL AT IT!

The Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty (BJC) believes in protecting your freedom of religion, no matter what you believe, even if the Southern Baptist Convention, the nation’s largest Protestant Christian denomination, decided in the 1980s that its leader “hobnobs” with liberals, then tried to starve it of funds that it has used to file over 140 legal briefs, including

A Giant Free-Standing Cross on Government Property ... “In American Legion v. American Humanist Association, the question for the U.S. Supreme Court concerned a free-standing 40-foot cross on government land in the middle of a major intersection in Bladensburg, Maryland. The BJC filed a brief arguing that the monument is unconstitutional because it represents a government endorsement of religion. In response to claims that the monument has an objective and secular meaning, the BJC countered: There is no more recognizable symbol of Christianity than the cross, and any attempt to deny that is offensive to Christians.” In 2019, the Supreme Court said the cross could stay.

A Muslim Ban ... “In Trump v. Hawaii, the Supreme Court addressed the White House's third attempt to limit immigration from certain Muslim-majority countries. The BJC argued that the government cannot enact laws designed to harm a specific religious group. But, in June 2018, the Court upheld the validity of the travel ban as within the president's immigration powers.”

Wedding Cake for a Same-Sex Couple's Reception ... “Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission centered around a bakery owner's refusal to make a cake for the wedding reception of a same-sex couple based on his religious beliefs, despite a state law requiring that businesses open to the public not refuse service due to LGBT status. The BJC filed a brief on behalf of the state of Colorado, explaining that laws like this one — cover discrimination against “disability, race, [religion], colour, sex, sexual orientation, marital status, national origin, or ancestry”— protect religious liberty. ... For example, another commercial baker could use these same arguments to refuse to create a cake for an interfaith couple, an interracial couple or a couple where one had been previously divorced.”

Religious Headscarf in the workplace ... “In 2015, the BJC and 14 other religious groups joined to defend the right of a Muslim woman to wear her hijab at work in Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores, Inc. The Supreme Court agreed.”

The group also opposes Government Funding of Faith-Based Organizations and School Vouchers but supports the Johnson Amendment and the Freedom of Religion Act (“legislation prohibits using immigrants’ religion … as a reason to keep them out of the U.S.”).

So it seems there was not all that much hesitation among the American colonials once they found themselves in control of their own civil liberties.

While the framers were framing away at the Constitution in Philadelphia, the Confederation’s Congress was busy in New York City, adopting

... the Northwest Ordinance which provided for the territorial government of the national domain north and west of the Ohio River and for its transition to statehood on an equal basis with the original states.

The Ordinance included an abbreviated bill of rights guaranteeing religious freedom in the first article. “No person demeaning himself in a peaceable and orderly manner shall ever be molested on account of his mode of worship or religious sentiments in the said territory.” ...

Two years later, the actual United States Congress would enact that Ordinance, but that line of thinking had apparently already been in some people’s minds, and it didn’t just come out of nowhere.

This, from Congress’s own website, describes the back-and-forth over the religious question:

The Constitution adopted by the Constitutional Convention in 1787 was largely silent on matters of religion. Nonetheless, matters of religious freedom remained on the Founder’s minds.

By 1787, a number of states had adopted constitutions containing some protections for religious freedom, though not all were as broad in scope as the ratified First Amendment.

Some state constitutions seemingly limited protections for religious freedom to certain types of believers. Furthermore, as discussed elsewhere, some of those states still supported religious establishments, even as other constitutional provisions limited some aspects of state establishments.

North Carolina’s constitution, for example, granted freedom of conscience and forbade an establishment of any one religious church or denomination in this State, in preference to any other, but further provided that the constitution did not exempt preachers of treasonable or seditious discourses, from legal trial and punishment.

AND NOT THAT IT MATTERS IN THE LONG ARGUMENT, BUT IT’S STILL WORTH MENTIONING, ONLY BECAUSE SO MANY CONSERVATIVES TEND TO POO-POO THE ACTUAL POPULARITY OF DEISM BACK THEN:

Increasingly the Founding Fathers abandoned traditional Christian religion and became what could be called deists. Many of these converts publicly maintained their original religious affiliations, choosing to avoid the censures that prominent deists like Jefferson, Franklin and Paine regularly received.

Deists abandoned the belief in the divinity of Jesus, the trinity, any notion of predestination, the Bible as the divinely inspired word of God, and state sponsored religion.

In short? Yeah, they didn’t agree with your particular religious views, but hey, no need to obsess on it! Live and let live! Believe what you want, and they’ll believe what they want!

IT WAS ALSO FORTUNATE THAT FOUNDERS OF COUNTRIES, MAYBE ESPECIALLY DURING THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT, WERE ABLE TO LOOK BACK INTO HISTORY FOR GUIDANCE:

WHOOPSY!! I’M SORRY, BUT YOU WERE THE WRONG KIND OF CHRISTIAN!! ... She made the mistake of being a Protestant Christian living in France while it was busy being a Roman Catholic Christian country! But the good news is, France stopped doing this to people with different religious views after their Revolution, once they had invented the guillotine and found other people to kill for completely other stupid reasons. (Wikipedia / Public Domain)

WOULDN’T YOU THINK IT MIGHT HAVE OCCURRED TO AMERICAN COLONISTS AT SOME POINT THAT AN AWFUL LOT OF US SEEMED TO HAVE BEEN MOVING TO THIS LAND SIMPLY TO ESCAPE FROM SECTARIAN STRIFE IN EUROPE?

Yes, there was that Spanish Inquisition — which was more like a Roman Inquisition, since much the pressure seemed to be coming from the Vatican to push the Jews around.

But come to think of it, much of the rest of it seemed to happen after Protestants started breaking away from being dominated, at first, by Catholicism — we seemed to have taken in plenty of Protestants escaping France, known as Huguenots, for example (Paul Revere’s father, Apollos Rivoire, was a Huguenot emigrant) — but also when all those breakaway denominations in Britain started getting nit-picky with each other, with arguments over which prayer books ought be used and whether or not one should baptize little babies before they get old enough to understand what they’re doing, and then the Puritans, “who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices”, but then the Congregationalists and Methodists and Anabaptists and Lutherans and Presbyterians and Jews and Quakers and Mennonites — but also the Shakers and the Holy Rollers — all, for some reason, seemed to be not that happy living in Europe.

(Yes, I suppose I should have included the Mayflower Pilgrims on that list, but then I saw an article suggesting that they didn’t move here for religious reasons but economic ones, although that might be only partly true.)

It’s true, many of the religions had a hard time coexisting once they arrived, but after a while, things started calming down, maybe them finally finding a way to do what they couldn’t do in Europe, which was tolerate each other. If anything, all these pilgrims came here to avoid factious rivalry, and maybe the nation’s authors chose to honor that need while designing their new home country.

BUT IN THE END, MADISON FINALLY SUCCEEDED IN MAKING A FEDERAL CASE OUT OF IT:

Throughout the ratification debate Antifederalists demanded that freedom of religion be protected. A majority of ratifying conventions recommended that an amendment guaranteeing religious freedom be added to the Constitution.

In recommending a bill of rights in the first federal Congress on June 8, 1789, Madison proposed that “the civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner or on any pretext infringed.”

He also proposed the “no state shall violate the equal rights of conscience.” The prohibition on states was removed by the Senate, while the restrictions on the federal government were combined and recast into what came to be the First Amendment:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

The exact meaning of this prohibition has not been easy to ascertain.

Which is exactly why I prefer Madison’s original wording, as it left less to the imagination.

But his proposed prohibition also on the states, which failed to pass the Senate, was finally rectified in 1868 with ratification of the 14th Amendment, saying no state “shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

IN DEFENSE OF THE CONSTITUTION’S INTENTIONAL ARMS-LENGTH APPROACH TO ORGANIZED RELIGION:

As Steven K. Green, teacher of law and history at Willamette University, points out,

... the United States became the first nation in history to abolish religious disqualifications from officeholding and civic engagement. The founders purposely created a nation that based its legitimacy on popular will, not on some higher power.

And in that same CNN article, Princeton history professor Kevin M. Kruse notes:

If the founders had not made their stance on this “Christian nation” issue clear enough in the Constitution and the Federalist Papers, they certainly did in the 1797 Treaty of Tripoli.

Begun by George Washington, signed by John Adams and ratified unanimously by a Senate still half-filled with signers of the Constitution, this treaty announced firmly and flatly to the world that “the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.”

That clear pronouncement may have been intended to dismiss any idea that it might be okay for the Muslim Barbary pirates to attack and capture Americans and take them as slaves, on religious grounds.

A FINAL THOUGHT TO TAKE AWAY, BEFORE WE MOVE ON:

So it turns out that, in guaranteeing freedom of religion (and freedom from it) in the Bill of Rights back in 1791, one thing the Founders did was examine what ideas states themselves had already been contemplating for their own constitutions in the years before, but it turns out they did not, after all, just casually consult some “stinking letter”, written by Thomas Jefferson some eleven years later!

AND, BY THE WAY, THAT “WALL” DIDN’T ORIGINATE FROM JEFFERSON’S 1802 LETTER. TOM BORROWED THE PHRASE FROM RHODE ISLAND FOUNDER ROGER WILLIAMS’S PAMPHLET PUBLISHED BACK IN 1644, IN WHICH HE REPORTEDLY (ACCORDING TO THE SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE) EXPLAINED HOW HE GOT KICKED OUT OF THE MASSACHUSETTS BAY COLONY:

The people of the Bay had left England to escape having to conform. Yet in Massachusetts anyone who tried to “set up any other Church and Worship” —including Presbyterian, then favored by most of Parliament — were “not permit[ted] ... to live and breath in the same Aire and Common-weale together, which was my case.”

Williams described the true church as a magnificent garden, unsullied and pure, resonant of Eden. The world he described as “the Wilderness,” a word with personal resonance for him. Then he used for the first time a phrase he would use again, a phrase that although not commonly attributed to him has echoed through American history. “[W]hen they have opened a gap in the hedge or wall of Separation between the Garden of the Church and the Wildernes of the world,” he warned, “God hathe ever broke down the wall it selfe, removed the Candlestick, &c. and made his Garden a Wildernesse.”

He was saying that mixing church and state corrupted the church, that when one mixes religion and politics, one gets politics.

He might have added that you also got the other way around, which would be equally as bad — that with the state, you might end up with nothing but religion. The wall doesn’t just keep the one separate from the other, but also the other separate from the one.

Just for fun, here’s a random sampling of countries that have state religions, with an emphasis on some reasons one might not want to live in one of them.

The 2008 Constitution of Maldives designates Sunni Islam as the state religion.

Only Sunni Muslims are allowed to hold citizenship in the country and citizens may practice Sunni Islam only. Non-Muslim citizens of other nations can practice their faith only in private and are barred from evangelizing or propagating their faith.

All residents are required to teach their children the Muslim faith.

Since 2014, apostasy from Islam [that is, leaving Islam for any reason] has been punishable by death.

It was described in its Declaration of Independence as a "Jewish state" – the legal definition "Jewish and democratic state" was adopted in 1985.

In addition to its Jewish majority, Israel is home to religious and ethnic minorities, some of whom report discrimination. ... [although] Israel is seen as being more politically free and democratic than neighboring countries in the Middle East.

According to the 2015 US Department of State's Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, Israel faces significant human rights problems regarding institutional discrimination against Arab citizens of Israel (many of whom self-identify as Palestinian), Ethiopian Israelis and women, and the treatment of refugees and irregular migrants. Other human rights problems include institutional discrimination against non-Orthodox Jews and intermarried families ...

… "Many Jewish citizens objected to exclusive Orthodox control over fundamental aspects of their personal lives." … approximately 310,000 citizens who immigrated to Israel under the Law of Return are not considered Jewish by the Orthodox Rabbinate and therefore cannot be married or divorced, or buried in Jewish state cemeteries within the country. …

According to a 2009 report from the US Department of State's Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, Israel falls short of being a tolerant or pluralistic society. According to the report, Israel discriminates against Muslims, Jehovah's Witnesses, Reform Jews, Christians, women and Bedouins. All 137 official holy sites recognized by Israel are Jewish, ignoring and neglecting Christian and Muslim sites.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is an Islamic absolute monarchy in which Sunni Islam is the official state religion based on firm Sharia law.

Non-Muslims must practice their religion in private and are vulnerable to discrimination and deportation. While no law requires all citizens to be Muslim, non-Muslim foreigners attempting to acquire Saudi Arabian nationality must convert to Islam.

Children born to Muslim fathers are by law deemed Muslim, and conversion from Islam to another religion is considered apostasy and punishable by death. Blasphemy against Sunni Islam is also punishable by death, but the more common penalty is a long prison sentence.

But not every problem living under religious tyranny involves prison and death; some of it has to do with whether you’d like to have a cocktail at the end of the day (although that might be loosening) or whether or not those of your gender are allowed to drive a car or go shopping while not in the company of a male relative.

The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran mandates that the official religion of Iran is Shia Islam and the Twelver Ja'fari school, and also mandates that other Islamic schools are to be accorded full respect, and their followers are free to act in accordance with their own jurisprudence in performing their religious rites. The Constitution of Iran stipulates that Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians are the only recognized religious minorities.

However, despite official recognition of such minorities by the IRI government, the actions of the government create a "threatening atmosphere for some religious minorities". Groups reportedly "targeted and prosecuted" by the IRI include Baháʼís, Sufis, Muslim-born converts to another religion (usually Christianity), and Muslims who "challenge the prevailing interpretation of Islam". ...

While there is no specific law against apostasy, courts can hand down the death penalty for apostasy to ex-Muslims, and have done so in previous years, based on their interpretation of Sharia’a law and fatwas (legal opinions or decrees issued by Islamic religious leaders).

There are laws against blasphemy and the punishment is death.

And here’s the latest news from Iran, by Sara Bazoobandi (via the Carnegie Endowment), who traces the history of the recent “wearing her hijab improperly” (you should click on that link) back to 1979:

In fact, shortly after Ayatollah Khomeini was declared the official leader of the Islamic Republic, he immediately addressed the issue of women’s clothing, announcing that women would be allowed to enter their workplaces only if they complied with the compulsory hijab.

Soon after Khomeini’s speech was published in March 1979, Iranian women took to the streets to protest the violation of their freedom of choice. The protesters were violently attacked by pro-Revolution forces that would later become the morality police — the organization that arrested Mahsa Amini last month.

And yet, in France, which has no official religion, there are laws prohibiting the wearing of a religious head scarf by women and girls in public. They explain that it’s because France has a tradition of protecting individuals from being pressured by groups, rather than protecting groups, apparently, from anyone. Go figure.

BUT HERE’S THE THING ...

Yes, one could argue that Christianity is not the same as Islam, and that we would never do that, but then, nor was my denomination the same as the Christian Church of England in early Virginia, with its Christian-on-Christian violence.

But the question is, why should anyone in this modern age have to live under the rules of somebody else’s religion … and even one of their own denomination … if they could choose not to?

Finally, this …

If you really believe your particular “Christian nation” would not take away anyone else’s religious freedoms, ask yourself this:

ISN’T THAT EXACTLY WHAT YOU’RE TRYING TO DO RIGHT NOW?